The Phoenix One Journals Stories from the dawn of RoadTrip America

More Phoenix One Journals>

October 4, 1998

Highway 395 from Ridgescrest to Bishop

Last Monday, I left on a trip. This might not seem remarkable if it weren't for a couple of beliefs I hold about myself. The first one is that I'm never not on a trip. I live on the road, like a latter day Odysseus. My only permanent residence is in cyberspace, and my home is the Phoenix, a wheeled contraption known in these waning years of the 20th century as a motorhome.

The other tenet I claim to hold is that life itself is a trip, a journey every one of us is on, whether we stay in one place or put wheel to pavement. The only thing static about existence is a naive belief in security and stability, as though there can be such things in a world that blows tops off mountains and is itself hurtling through space at speeds so fast that our bodies are built to ignore the movement altogether.

So how did I manage to leave on a trip if I was already traveling? I guess you could say it was like the Pope's hats. He wears one inside, and he puts on another when he goes outdoors. If it rains, he's got a third one, and a tall pointed one for official duties inside cathedrals. One way or another, he's always got a hat on, and sometimes he's wearing three.

I was already on a trip because we all are. My husband and I added a layer by deciding to live in a motorhome and by keeping the wheels rolling for over four years. Life was a double trip, even when the wheels slowed and we found ourselves on a short tether, linked to Los Angeles by a project that was accomplished more easily with convenient access to people and companies rooted there.

For nine months the project kept us on a short lead. We shopped at the same supermarkets, made appointments we knew we'd be in town to keep. Most indicative of all that we'd slipped into a "to and fro" lifestyle was the undeniable fact that we had to say good-bye when we were finally ready to leave. By the time we actually rose out of the Los Angeles basin on Interstate 15, I felt like the lid on a can of old paint. I'd been pried loose.

"We're heading north," we told people, which in Southern California begs the question: "Going up the coast?" And I thought we would follow that spectacular track that traces the edge of the continent. Highway One is the stuff of legend, a road whose glory will live long after the inevitable shift and crunch of tectonic plates render it as invisible as Atlantis. I can see the titles now: "The Lost Highway of the Far West," and "The Road to Paradise: Fact or Fiction?"

It wasn't until people started asking that I started to consider the other possibilities. "We could go north on an inland route," I said to Mark. "Why not 395?"

Highway 395 passes Los Angeles eighty miles to the east, connecting southern California with Canada by way of Nevada, Oregon and Washington. To pick it up from Los Angeles, you have to climb the San Gabriel Mountains and descend to the desert beyond. The road shoots straight up the Owens Valley, an arid, flat expanse that once boasted a lake big enough for steamboats until the city of angels reduced it to a puddle.

Highway 395 would probably have the same boring reputation as the long, flat stretch of Interstate 5 that links Los Angeles with San Francisco, but it escapes such labeling because it's the road used by skiers, hikers, gamblers, fishermen, and mountain climbers to get to such sporting and gaming Meccas as Mammoth, Yosemite, Lake Tahoe, Reno, and any number of other renowned vacation destinations. Highway 395 is the road of holidays and honeymoons, the corridor leading to the best summer vacations I ever spent. When I was a teenager, my parents took my siblings and I backpacking in the Sierras every July, and no similar expeditions have ever been as wonderful. Can you beat being sixteen and basking on the edge of an alpine tarn? Freeze-dried succotash will ever be ambrosia.

With such destinations as Tuolumne Meadows and June Lake on your mind, it's easy to zip past the signs and towns on the valley floor, stopping only for a root beer in Big Pine, a burger in Bishop. Mark and I decided, as we began our trek up the road to wonderful, to pause a little at lesser known spots along 395, and we began our moseying in Ridgecrest, a high desert town on the edge of China Lake Naval Weapons Center.

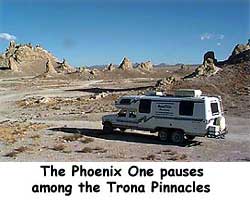

Ridgecrest was gearing up for a fair, which meant that the RV park next to the fairgrounds was chock full of vendors. It seemed to be the only campground in town, so we headed north on the road to Death Valley. We hadn't gone far when we saw a Bureau of Land Management sign pointing to something called the Trona Pinnacles.

"I've never heard of the Trona Pinnacles," said Mark, and I was equally unaware of their existence. After only a mile of washboard, the pinnacles broke the horizon. They were irregular points jutting out of low hills, and from a distance they looked like cities Martian gnomes might have built.

When

we reached the spires, they towered over us. Now they seemed like the

huge serrated teeth of some leviathan whose jaw was buried here eons ago.

The sun was fast disappearing behind the jagged horizon, and we watched

it turn the tall stones orange and purple. Before the light disappeared,

we parked the Phoenix between two titanic canines and slept soundly in

the monster's mandible.

When

we reached the spires, they towered over us. Now they seemed like the

huge serrated teeth of some leviathan whose jaw was buried here eons ago.

The sun was fast disappearing behind the jagged horizon, and we watched

it turn the tall stones orange and purple. Before the light disappeared,

we parked the Phoenix between two titanic canines and slept soundly in

the monster's mandible.

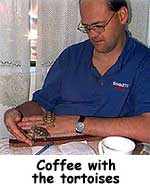

Rising

before dawn, we returned to Ridgecrest, where we had an early morning

appointment to meet Millie Michel, who has lived in the desert since 1971.

She's known for rescuing injured and homeless desert tortoises, and we

were eager to meet her and her special charges.

Rising

before dawn, we returned to Ridgecrest, where we had an early morning

appointment to meet Millie Michel, who has lived in the desert since 1971.

She's known for rescuing injured and homeless desert tortoises, and we

were eager to meet her and her special charges.

Now that I've done it, I can't imagine a more lovely way to enjoy a cup of coffee than in the company of five baby tortoises. Exact replicas of their five-gallon parents, the month-old hatchlings were the size of yoyos. Finding themselves outside the plastic tub they called home, they rambled about the table, searching eagerly for an escape route to the larger world. "I'd let them outside," Millie explained, "But the big black birds will eat them." In a year or so, the babies will be tough enough to survive. In ten years, they can breed. They might live to be a hundred, especially if they stay away from cars.

"People

actually swerve to hit them on the road," said Millie. Her grandson

recently rescued a highway casualty, a thirty-year-old female who'd suffered

a cracked shell and a broken leg. Thanks to Millie's care and the innovative

techniques of a local veterinarian, Heather doesn't limp any more, and

her shell is unobtrusively patched with silicone mesh.

"People

actually swerve to hit them on the road," said Millie. Her grandson

recently rescued a highway casualty, a thirty-year-old female who'd suffered

a cracked shell and a broken leg. Thanks to Millie's care and the innovative

techniques of a local veterinarian, Heather doesn't limp any more, and

her shell is unobtrusively patched with silicone mesh.

Bidding

farewell to Millie, we headed north once more. We pulled into a rest stop

near Coso Junction and parked next to a small RV whose smiling owner emerged

to say hello. "I've been on tour in an RV since 1991," said

Russ Richard. "I'm a paraglider and hang glider pilot."

Bidding

farewell to Millie, we headed north once more. We pulled into a rest stop

near Coso Junction and parked next to a small RV whose smiling owner emerged

to say hello. "I've been on tour in an RV since 1991," said

Russ Richard. "I'm a paraglider and hang glider pilot."

"I

have an e-mail account I can access from any Web browser," he said.

"I use public libraries, cyber cafes, Kinko's, and sometimes even

university libraries. Oh, and of course friends and relatives. My e-mail

account is free, and access is free or cheap. I don't even own a computer."

"I

have an e-mail account I can access from any Web browser," he said.

"I use public libraries, cyber cafes, Kinko's, and sometimes even

university libraries. Oh, and of course friends and relatives. My e-mail

account is free, and access is free or cheap. I don't even own a computer."

While we were chatting, another couple approached. "I've seen you on the Web," said the man, "And now I get to see you in person."

Was it really less than three years ago that social activists worried that Internet access would be available only to the wealthy, and that "http://" and "URL" were gobbledegook? It's been a fast thousand days.

As we continued moseying up 395, we caught sight of another intriguing Bureau of Land Management sign. "Fossil Falls" this one read, and suddenly we just had to take a look. A short trip up a dirt road and a short walk brought us to another remarkable opus of nature, a black rock canyon sculpted by an ancient volcanic flow.

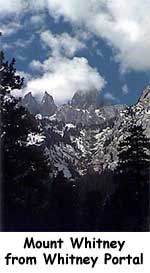

As we continued our beeline up 395, the Sierras rose on the left, pristine under a sparkling blanket of early snow, most of which had fallen the night before. At Lone Pine, we turned left on Whitney Portal Road.

The

road wound first through the stark red rocks of the Alabama Hills, and

then rose sharply into the mountains. The Phoenix One crawled up the switchbacks,

bringing us at last to the awesome spot where Mount Whitney rises directly

over the road, framed in the pine trees of Whitney Portal, its peak shrouded

in clouds. We walked through the forest near the Mt. Whitney trailhead,

descended once more to the valley floor, and drove on to Bishop.

The

road wound first through the stark red rocks of the Alabama Hills, and

then rose sharply into the mountains. The Phoenix One crawled up the switchbacks,

bringing us at last to the awesome spot where Mount Whitney rises directly

over the road, framed in the pine trees of Whitney Portal, its peak shrouded

in clouds. We walked through the forest near the Mt. Whitney trailhead,

descended once more to the valley floor, and drove on to Bishop.

Virginia

City, Nevada

October 4, 1998