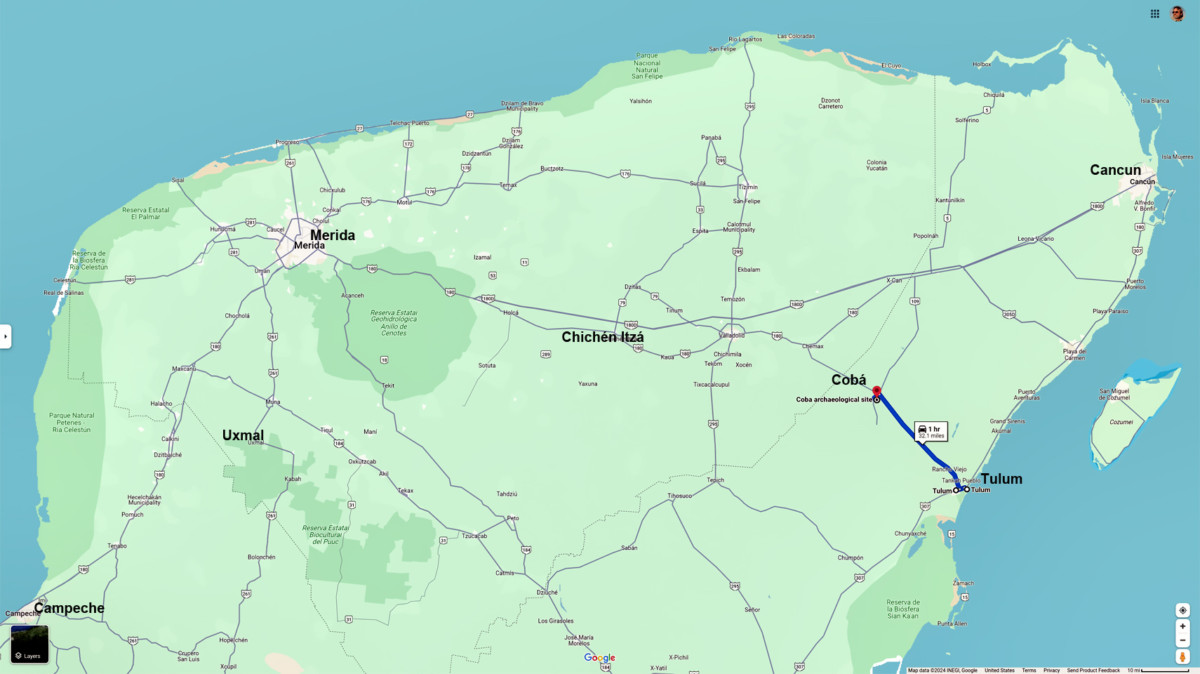

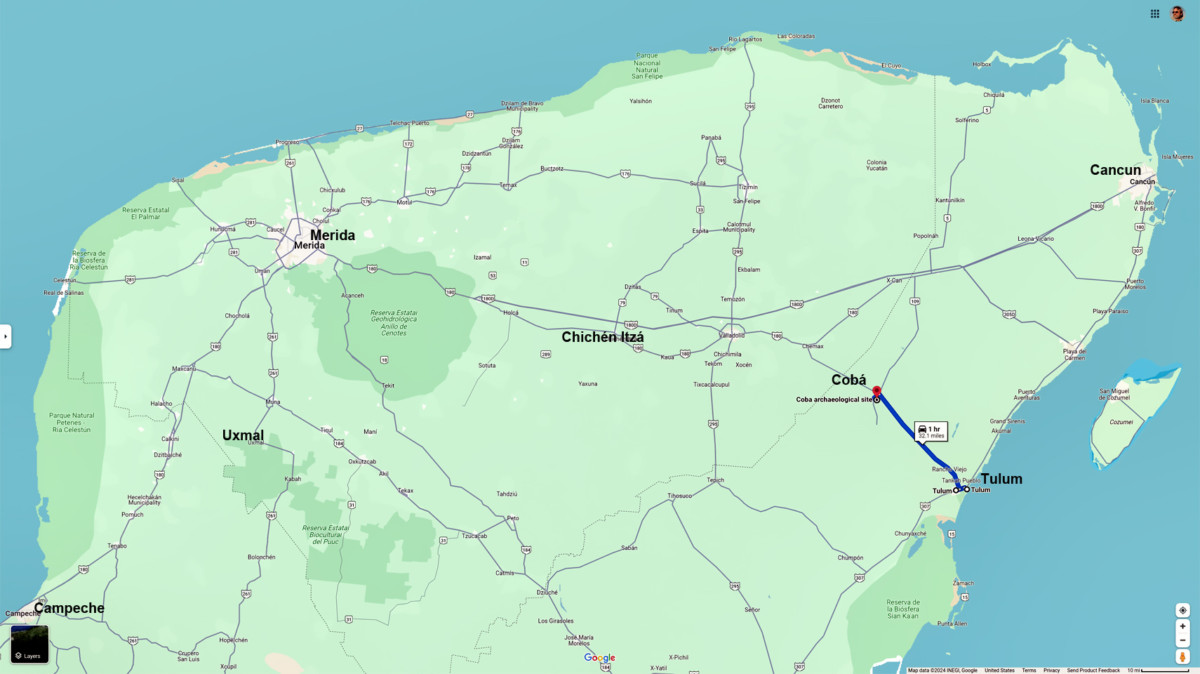

On the 13th day of our road trip, we spent the morning making a follow-up visit to the Mayan ruins at Tulum. Our plan for the afternoon called for a visit to a place called Cobá, a large Mayan site just 30 miles away to the northwest. Known as the City of the White Roads, Cobá is the fifth most popular Mayan ruin in Mexico, at least in terms of visitor numbers–although I was fairly sure that had more to do with the proximity to Cancun than it did with the quality of the architecture.

We’d already booked a second night at the Maison Tulum; (with that French bakery on the ground floor, we were certainly in no hurry to leave).

Maison Tulum, Google Street View

That left the rest of the day free, giving us plenty of time to drive to Cobá, explore the ruins, and still make it back to Tulum in time for dinner.

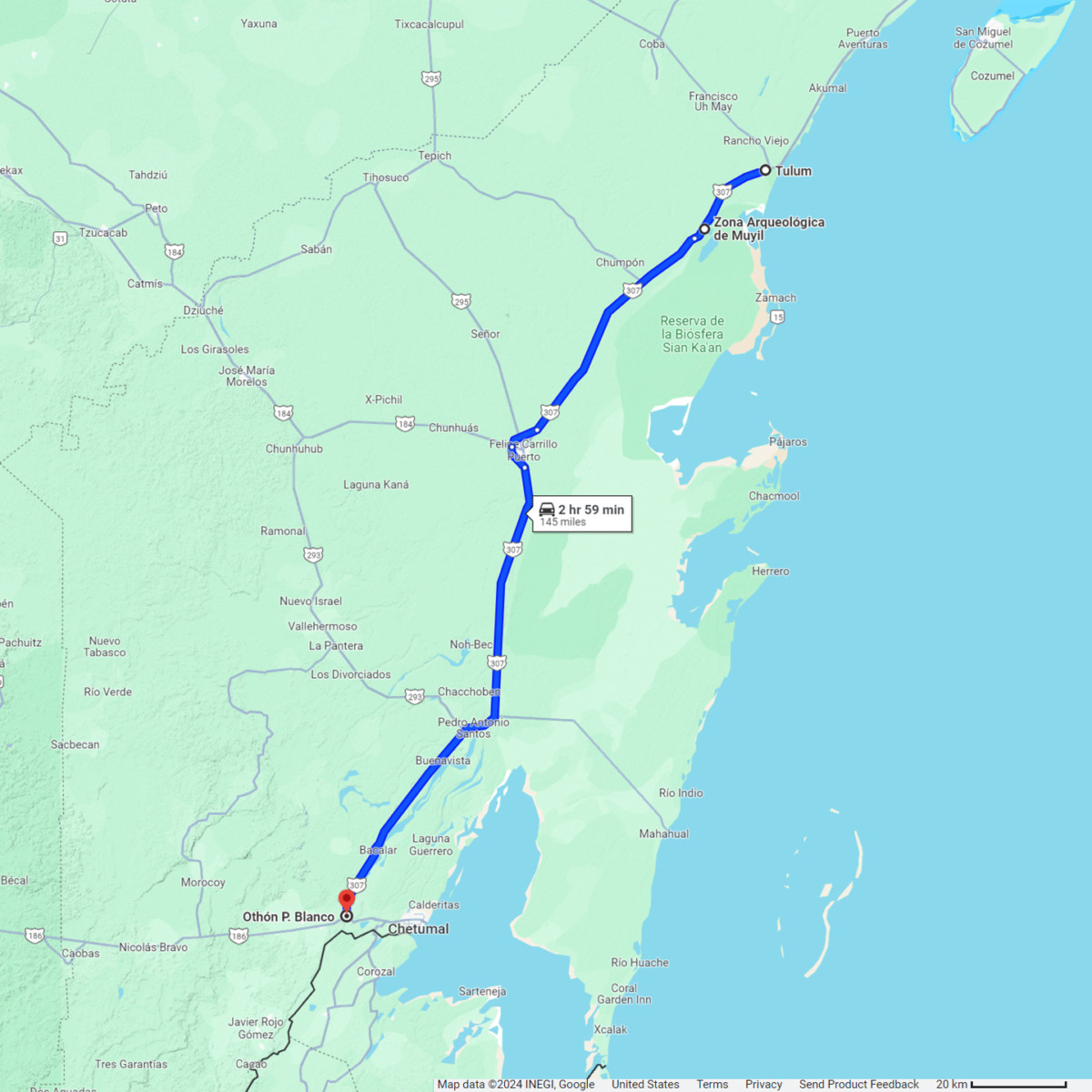

The route couldn’t have been simpler: a straight shot on MX 109, a Quintana Roo State Highway.

Tulum to Coba

That meant we’d be contending with potholes, livestock, and the ubiquitous topes (killer speed bumps) but at this point, all that was par for the course.

Transit Police on motorcycles, snuck up beside us at a stop sign.

COBÁ

We arrived at the archaeological park a little after 1:00 PM. There’s a village adjacent to the ruins, but very little infrastructure.in the park itself. A row of tour buses sat idling on one side of the lot, engines running to keep their AC going, but there were no more than a dozen private cars in view, and some of those probably belonged to staff. This was October, the off season, but I got the sense that the lack of private cars was typical, that the majority of Cobá’s visitors tend to come on those buses, and not on their own.

Park Entrance, ruins of Cobá

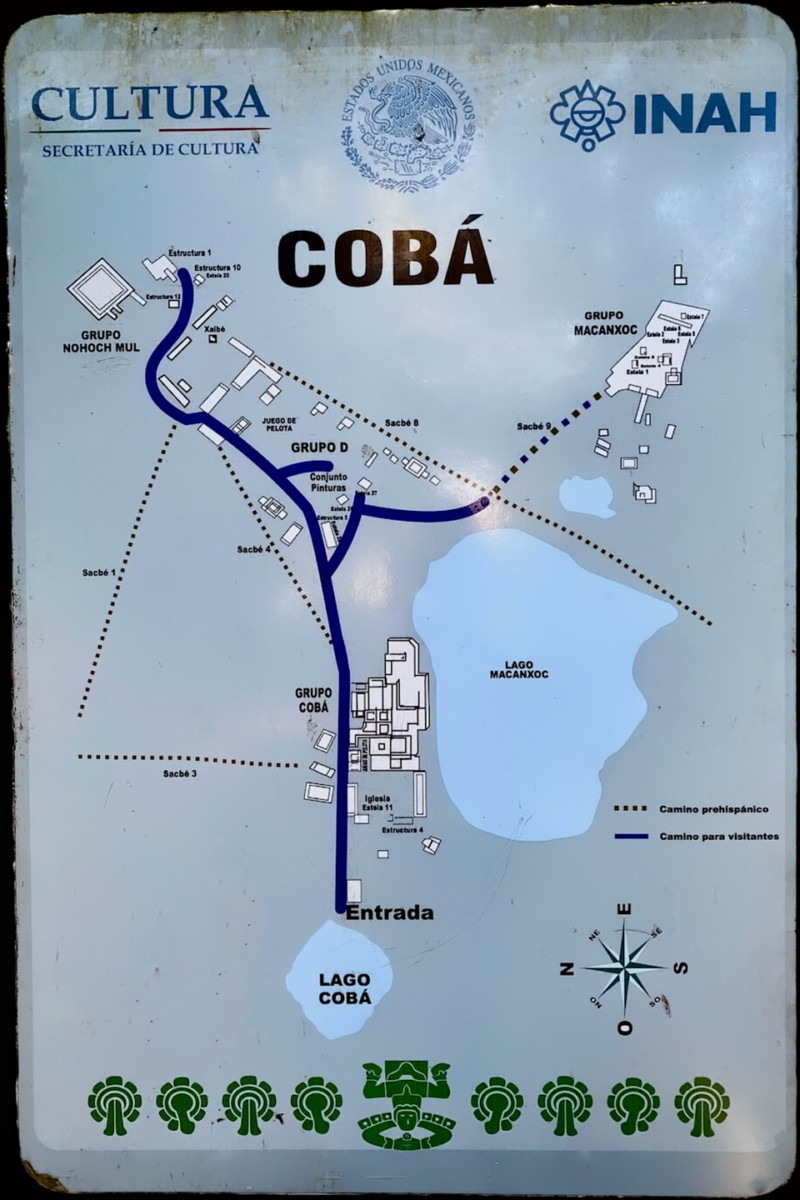

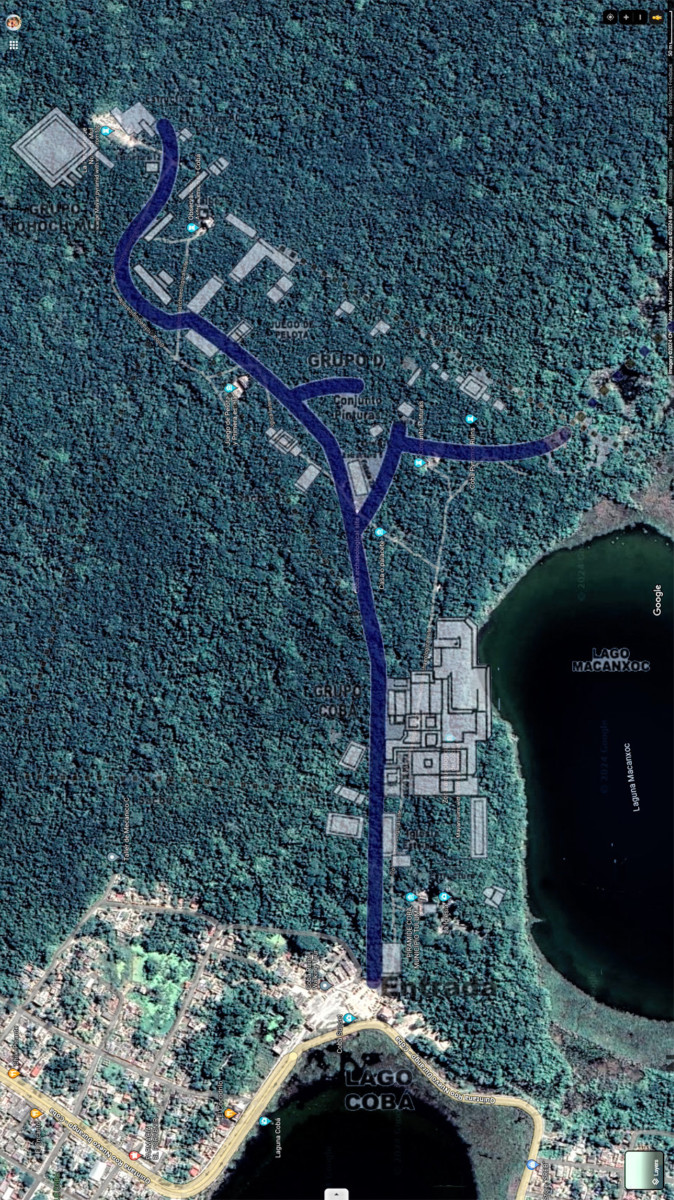

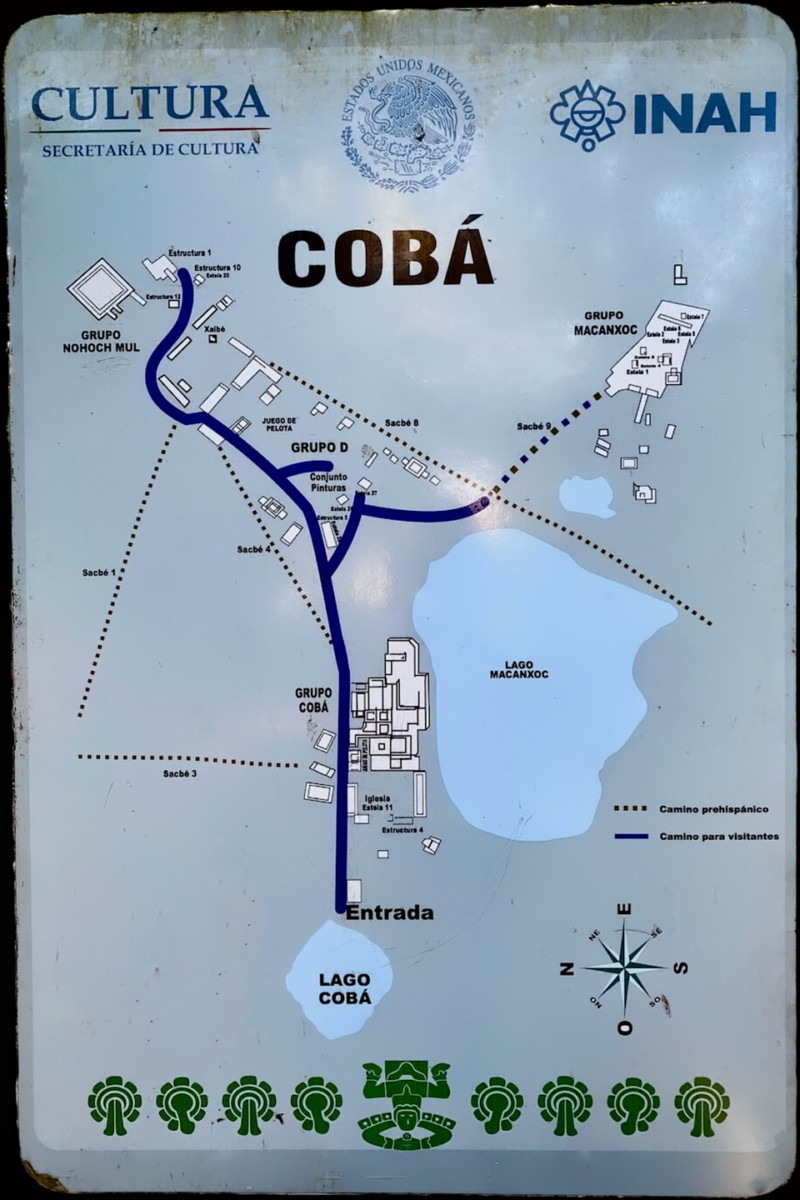

Cobá: Site Map (INAH)

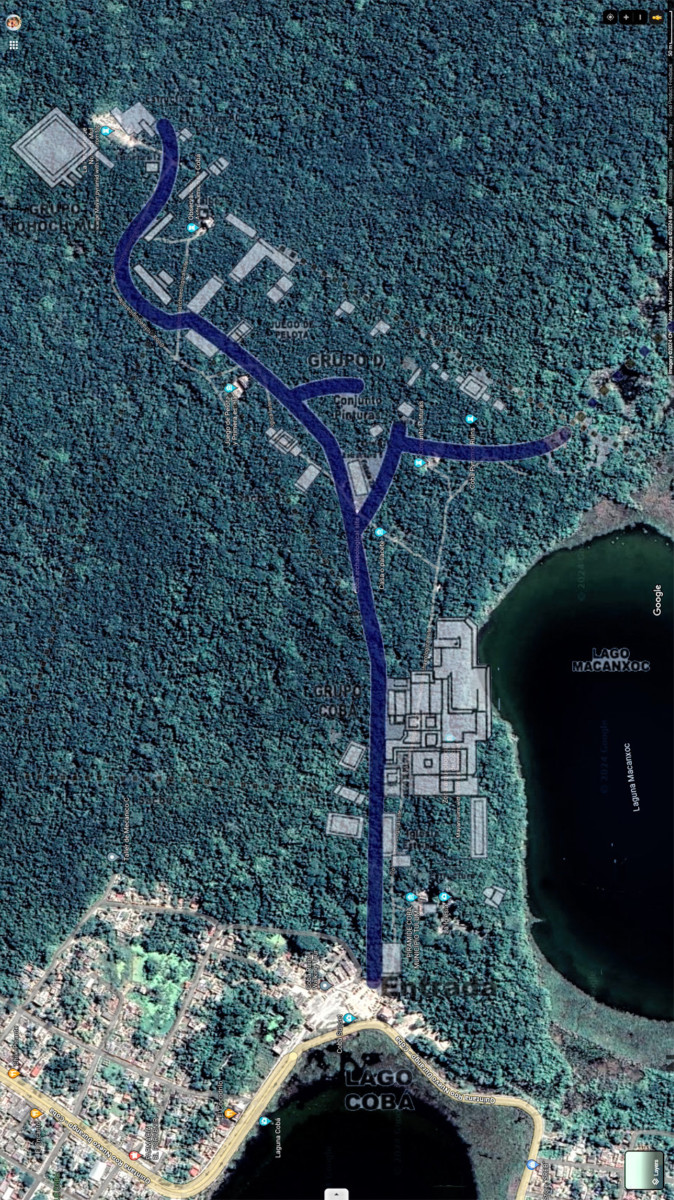

Site Map composited with Satellite View

The first thing we saw when we walked in was a bicycle rental concession, along with a fleet of pedicabs, all staged near the entrance, and doing a booming business. We rather quickly found out why. In it’s day, Cobá was one of the largest of all Mayan cities, with a population estimated to have been more than 50,000 people, spread out over several square miles. Unlike the other sites we’d visited, there wasn’t one central area where all the most interesting structures were clustered. The attractions at Cobá were spread out, just like the original old city had been, so there were actually four different groups of ancient buildings, separated by as much as two miles! On the plus side, the old Mayan roads, the sacbeob, still connected the various sections, and portions of them are kept in good enough shape to use as bike paths.

Most visitors to Cobá rent bicycles to tour the extensive ruins

Other visitors prefer to be carried

Many of the people we saw returning their bikes after finishing their tour looked like they’d just run a triathlon, puffing and panting, dripping sweat, and red in the face–which was hardly an endorsement of the experience. October in the tropics can still be quite warm. With all the rain, the day was humid to the point of stifling, and the path was lined by thick jungle growth that blocked off any hope of a breeze. Honestly? Mike and I didn’t even ask about the bicycle rentals. We went straight to the Pedi-cab stand, and sat ourselves down in the first available. Our designated pedal-pusher was a young guy named Francisco, who was clearly in better shape than either of us old gringos. He offered us a two hour circuit of the ruins for 200 Pesos (a little over $10). Sounded downright cheap to me, so off we went!

Me and Mikey chose the Pedi-cab option; (hence, Mike’s toothsome smile).

Francisco was quick to point out that he wasn’t a guide. Official guides had to be certified, and it wasn’t so easy to get that credential. He would nevertheless do his best to answer any questions we might have, and he’d let us know what we were seeing as we made our way through the site.

The first stop, not far from the entrance, was a Ball Court, with sloping sides, and stone goal rings still in place. Every Mayan city had at least one of these; according to Francisco, Cobá had two of them. This was the smaller court, probably used for practice, or more intimate contests. Players on opposing teams tried to knock a rubber ball through the goal without using their hands or feet.

Ball Court #1, flanked by a platform with stone steps. The game was a merger of sport, politics, and religion. In some contests, the losing team was sacrificed to the gods!

Cobá was quite a big deal back in its heyday, from 600 AD to about 1000 AD. Being the largest city in the area gave them the resources to dominate their neighbors, and that’s exactly what they did. They demanded tribute from all the lesser Lords, and secured their privileged position by forging close alliances with their most powerful rivals, the kings of Tikal, Dzibanche, and Calakmul. It’s quite probable that they secured those ties through intermarriage of the noble houses. Based on inscriptions found on many of the stelae at the site, a great many of the rulers of Cobá are thought to have been women. It’s important to note that even though major new construction ceased after 900 AD, Cobá was not abandoned at that time. The city remained occupied, and the original structures were still being maintained well into the 14th century, almost up to the time of the Spanish Conquest. When Chichén Itzá started its rise to prominence, Cobá was already beginning its slow decline, yet it remained a force in competition with the mighty Itzá for at least a century.

Cobá was a religious center, with the largest, finest pyramids and temples in the area, and it was also at the center of a thriving trade network. The Maya never quite developed the wheel, and they had no draft animals, so everything that required transport had to be carried on the backs of humans. The sacbeob, the White Roads, were raised pathways that spread out from Cobá’s ceremonial and administrative centers like a web. The name came from the layer of crushed white stone spread along the path to reflect moonlight, making it easier for the bearers to move their loads in the cool of the night. Within the city, the sacbeob connected hundreds of residential clusters, each cluster consisting of fifteen houses built atop a raised platform. Outside the city, the White Roads extended for as much as 100 km, connecting the many smaller Mayan cities and towns that traded with Cobá, and owed fealty to the kuhul ajaw, their divine ruler.

The thought that we were rolling along those original sacbeob was very cool; there were more of them in evidence here than at any other site in the Mayan world. The crushed white stone that once defined the pathways is long gone, but since the park closes at 5:00, the only people who might benefit from reflected moonlight are people who–let’s face it–shouldn’t be out there in the first place.

The Pyramid of the Painted Lintel, with a staircase up one side.

Climbing is not allowed, so the close view of the painted stones was taken with a telephoto lens.

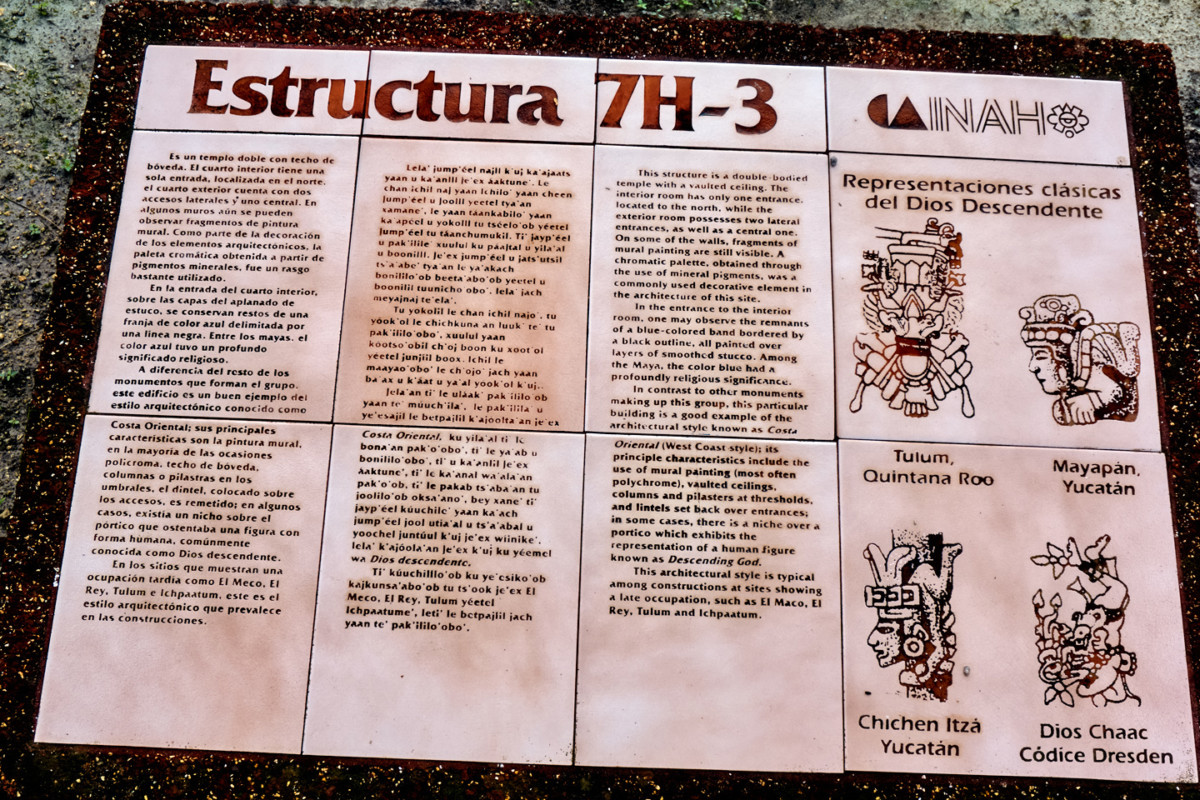

We pedaled along for 20 minutes or so, then got out and walked to the next major grouping of structures, centered around a squat, truncated pyramid topped by a blocky temple. This was the “Pyramid of the Painted Lintel,” so called because of the stones above the temple doorway that are still coated with the original red and blue-green paint. The temple and its lintel was protected by a palm thatch roof supported by wooden poles. According to Francisco, the roof was a recent addition, put there to shield the ancient paint from direct exposure to the weather.

Francisco was well accustomed to the task of pedaling visitors around the ruins, but this particular day was extra humid from all the recent rain, and we were on a section of path that went slightly uphill. The poor guy was struggling, standing up on the pedals to put all of his weight into the down strokes, and sweating buckets. I insisted that he pull over and take a break while we explored the next set of ruins on foot.

The architecture was classic Peten style, influenced by the early Mayan city-states in northern Guatemala. The structures are old and worn, blocky, lacking the flair and the artfully restored embellishments that characterize the more famous sites, like Chichén Itzá and Uxmal.

Cobá wasn’t opened up to tourists until the 1980’s; only a small part of the old city has been cleared, and much of that is already overgrown again, with jungle trees sprouting from the steps and platforms.

A short distance away was the main Ball Court, which was definitely bigger than the first one.

There were carved stone panels and other sculptures, including a stone skull, very worn, mounted flush with the ground at the center of the court.

Most interesting was a large panel of glyphs, a record of dates and other details relevant to the contests that took place here.

One of the two goal rings has a section broken out, which is actually typical. They’ve found at least a hundred Mayan Ball Courts in the Yucatan, and only a handful had goal rings still in one piece. At some Mayan sites, broken rings have been replaced with intact replicas. Here, they did no such thing.

Just beyond the main Ball Court was a four-tiered conical structure known as the Xai’be Pyramid, often called the Iglesia (the church). Round buildings are unusual in the Mayan world, and are often associated with the observation of celestial events, and the forecasting of solstices and other seasonal phenomena. The Xai’be Pyramid was thought by some to have served that purpose, in the manner of the famous Caracol at Chichén Itzá, but, according to the archaeologists, no evidence has been found that would support that theory. As far as we know, Cobá’s Iglesia was never anything more than a monument to a ruler’s ego.

The Xai’be Pyramid, also known as the Iglesia (the church)

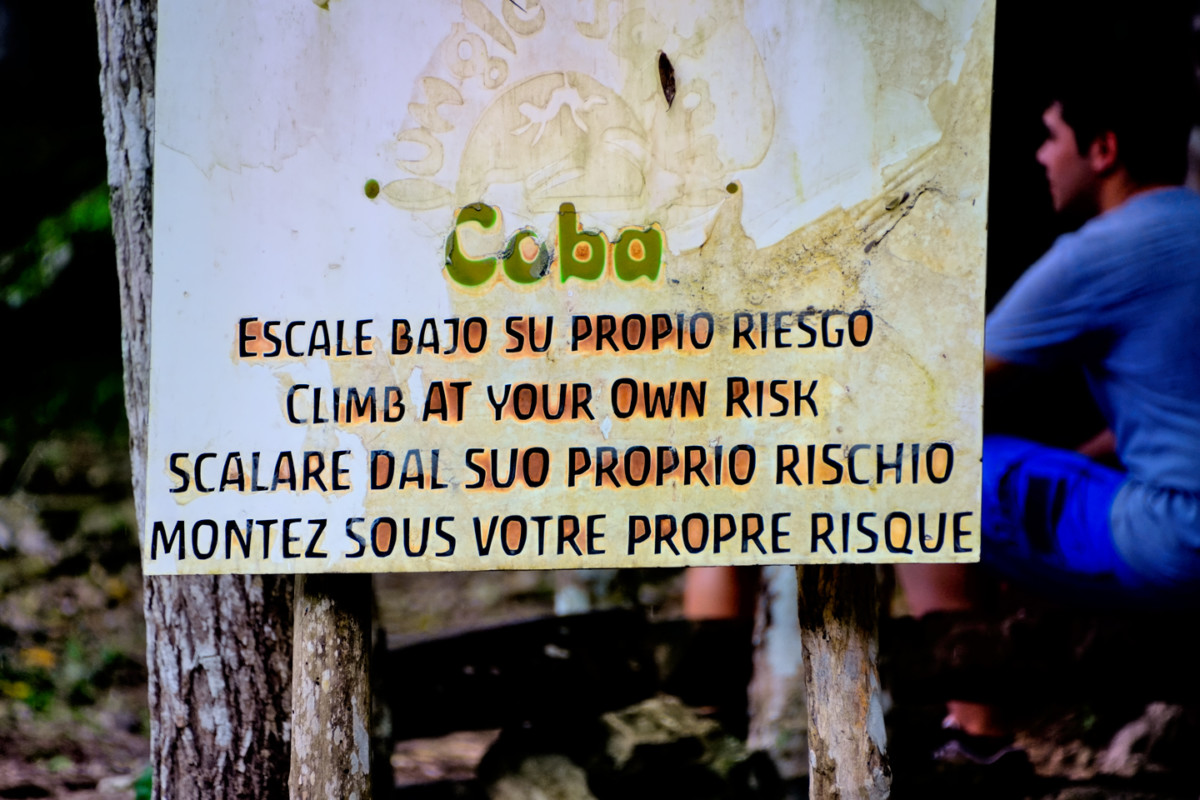

A stone’s throw from the Iglesia was the Ixmoja Pyramid, the largest building in Cobá. Rising 140 feet from its base, the Ixmoja is the second tallest pyramid in the entire Mayan world, and it’s the main reason why most visitors come to Cobá in the first place. Why is it so popular? Because they still allow visitors to climb the darned thing, 130 very steep steps, all the way to the top, where you’re rewarded with a killer view of the surrounding countryside. Pyramids at most of the Mayan sites in Mexico, including the famous Castillo at Chichén Itzá, have been off limits to visitors for decades, for safety reasons, as well as to protect the monuments from the wear and tear caused by millions of trampling feet. If “climbing a Mayan pyramid” is an item on your bucket list, Cobá is one of the very few places where you can still scratch that itch.

Why do I not have pictures from the top? Because, I regret to say, we didn’t make the climb. We stood there and watched for a bit, but in the end, we elected to skip it. When you get to a certain age, you have to be honest with yourself about your limitations, and about the fragility of old bones. My sense of balance isn’t what it used to be; I get dizzy on ladders, and even worse when looking down from high places. I imagined myself clambering up (and then back down again) all of those steep stone steps, climbing in a conga line with all those other people, and, if I’m being honest? It really didn’t look like fun.

Visitors to Cobá, climbing the Ixmoja pyramid.

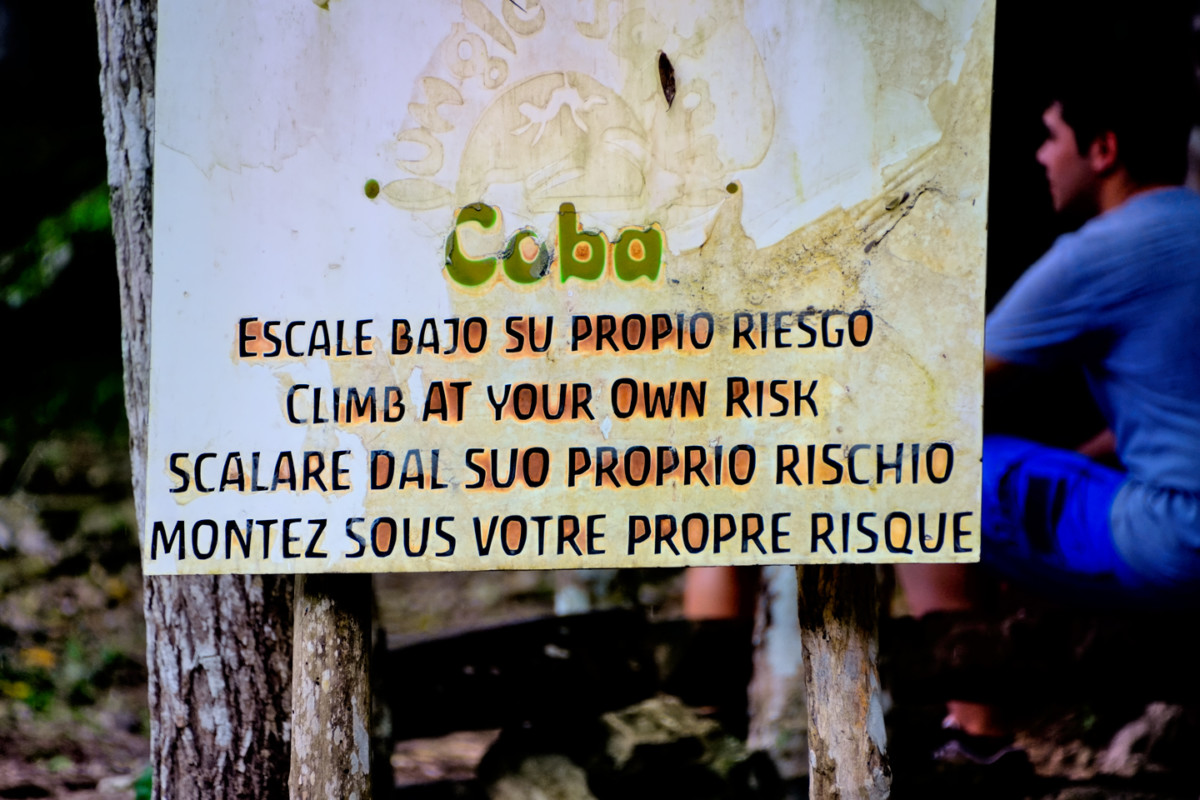

A warning sign states “Climb at your own risk,” in Spanish, English, Italian, and French.

There is a guide rope fixed in place, the one and only concession to visitor safety. A fall from the top could be fatal!

Cobá is known for its stelae, the flat standing stones carved with intricate designs commemorating important persons and events. The glyphs on the stelae, to the extent that they are still legible, tell the story of Cobá’s noble houses, the wars, the alliances, and the succession of rulers (the cabbages and the kings), complete with dates that they’ve been able to translate. There are several groups of stelae in different sections of the ruins, protected from the weather by rustic palm thatch roofs. To the untrained eye, most of them don’t look like much, but for the Maya scholars, they speak volumes.

There was still a lot more to see, including a large set of buildings known as the Macanxoc Group, but that would have meant pushing our Pedicab driver well beyond the two hours we’d agreed to. The poor guy was pretty well whipped, and Mike and I had put in quite a long day ourselves, so we called a halt. We thanked Francisco for his services, and threw in an extra 200 Pesos as a well-deserved tip.

The drive back to Tulum was uneventful (just the way we like it), and in what seemed like no time at all, we were back at our hotel, sipping on a cold brew. After dinner, we spent a pleasant evening in our room, plotting our next move. We were close to the mid-point of our expedition to the Yucatan. We’d been to Palenque, Uxmal, Chichén Itzá, Tulum, and now, Cobá. That was the whole top five, so it was time to shift gears, and start exploring some of the sites that are less well known. With dozens of possibilities to choose from, narrowing down the list was a challenge.

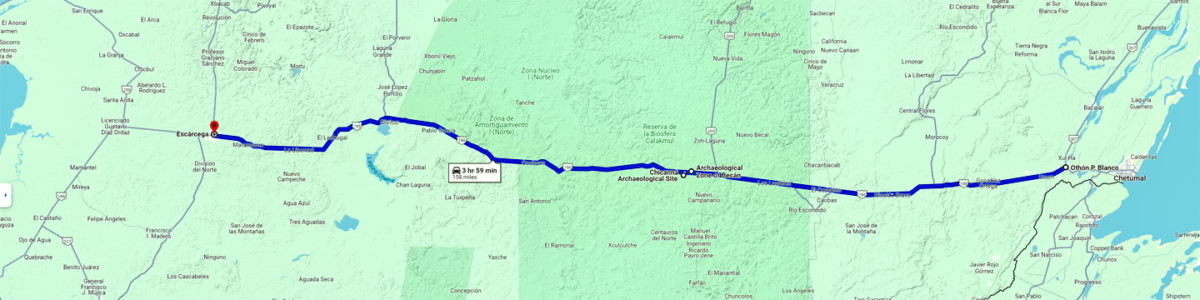

We definitely wanted to go back to Campeche. We’d passed through it much too quickly when we were on our way to Merida the week before, and I’d promised myself a closer look at the place before we left the area. With that in mind, we spread out our maps, and plotted a route from the Riviera Maya to the opposite side of the peninsula, by way of Escárcega. That would not only complete our circle around the Yucatan, it would give us easy access to at least a half dozen Mayan cities that we’d be passing along the way.

Next up: Day 14, from Tulum to Escarcega

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote