|

Road Trip Washington, D.C.

SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHING NEW: THE SMITHSONIAN'S NEW MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

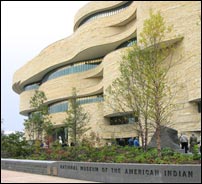

The building itself is imposing, a large ship-like edifice constructed of wheat-colored limestone. In front, a water feature follows the graceful curves of the façade, and nearby, a "constructed wetland" mimics a natural pond. Around one side, tobacco plants are blooming next to corn stalks that have finished producing for the year. A long line of people is waiting to enter through glass doors etched with native sun symbols.

This is the National Museum of the American Indian on a Sunday afternoon. The museum opened its doors for the first time less than a month ago, so the line isn't surprising. The surprises, I am about to discover, are inside.

The NMAI is the latest member of the Smithsonian's impressive lineup of treasure houses in Washington, D.C., a long-waited addition to the collection often referred to as "America's Attic." Until its opening, exhibits about Indians occupied space in the Natural History Museum, but now, at long last, "the first Americans" have scored their own space.

Fortunately, the line moves quickly, and I'm inside before I finish admiring the "grandfather rocks," large boulders that form part of the exterior landscape of the museum. After a security guard has poked my camera case with his wand I find myself standing on the edge of a large circle under a high rotunda. Light passing through a window paned in prisms casts rainbows on the wall.

Beyond the rotunda are the first exhibit cases, but there are also signs pointing to the museum restaurant. It may not be proper museum etiquette to eat first, but I'm hungry after a trek across Washington aboard the Metro and a walk past the other museums on the Mall. And the cafeteria-style Mitsitam Cafe is part of the museum experience, I tell myself, with menu items reflective of Indian cultures from South America, Meso America, the Northwest Coast, the Northern Woodlands, and the Great Plains. Passing up such delicacies as a lobster salad roll (Northern Woodlands) and cream of peanut soup (South America), I settle on buffalo chili with pinto beans on fry bread (Great Plains). The restaurant's tables have a view through picture windows of the water feature outside, and the food, pleasant enough, might well even be authentic.

|

|

Even though the line to get inside was a block long, the museum doesn't feel overly crowded. A circular stairway leads to the other levels, and there's also a bank of elevators. There doesn't seem to be a prescribed pattern for experiencing everything, so, on the third floor, I wander into what turns out to be the gallery for "changing exhibitions." It's currently occupied by the works of George Morrison and Allan Houser, artists who worked from the mid-1930s through the 1990s.

Also on the third floor is a large gallery called "Our Lives." Inside, it's divided into eight sectors, each dedicated to a different Indian community from the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean. In the Igloolik exhibit, footage of a man on a snowmobile is running on a large, high-definition monitor. As he zooms along, he's describing life in the Canadian arctic. Display cases on either side of the monitor contain art and artifacts chosen by Indian curators to reflect Igloolik culture. The other displays in the gallery are similar, each one created by the community it represents. In other words, if you're looking for traditional museum depictions of how Indians lived in the olden days, you won't find it here. You won't even find the names you recognize - most tribes now call themselves by their own names, not those imposed by European conquerors.

The fourth floor houses two large galleries, "Our Peoples" and "Our Universes." "Our Peoples" focuses on history. Possibly the most impressive display is a gigantic glass case full of gold objects. Labels are notably absent, but it's not difficult to recognize the style of Central and South American masks, amulets, and jewelry. Also in the case are the iron spears and swords wielded by conquistadors. Another huge case is full of guns, and another displays Bibles translated into different Indian languages. As in the "Our Lives" gallery, sections dedicated to specific nations -- Tohono O'odham, Seminole, Ka'apor, Kiowa, to name a few -- reveal historical events from Indian perspectives.

"Our Universes" has a ceiling reminiscent of a planetarium -- dark and star-filled. This gallery is dedicated to creation stories and philosophy. As in the other halls, the exhibits have been created by eight native communities including the Lakota (South Dakota), the Quechua (Peru), the Pueblo of Santa Clara (New Mexico), and the Hupa (California). An animated myth about how Devil's Tower in Wyoming was formed by a girl who turned into a bear is running on a video monitor. The story of "How Raven Stole the Sun" is told in a case nearby.

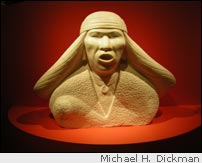

Outside the galleries on each floor are large glass-walled displays of art and artifacts including dolls, projectile points, clay figurines, baskets, ceremonial raiment, and ceramics. The quantities are impressive -- hundreds of spear and arrow points have been arranged to look like schools of fish, and the case of terra cotta figures holds an array other museums can only dream about. If explanations are few, quality and quantity go a long way toward making up for it.

I thought about the museum during the few days I remained in Washington, remembering its beauty and wondering about choices its curators had made. I wish I could ask an Indian about it, I kept thinking. Maybe then I could get some answers.

On the plane back home, I mentioned the museum while chatting with my seatmate. As soon as I said it, the man sitting next to him leaned forward.

"Did you like it?" he asked.

"I did," I said. "It was beautiful."

"I was at the opening," he said, and he went on to tell me that he was a member of the Tohono O'odham nation in Arizona, one of the communities represented in the "Our Peoples" gallery. He explained the meaning of the name (People of the Desert) and how it has replaced Papago, a term imposed by outsiders meaning "bean eaters."

"What do you think of the museum?" I asked, but he never told me. He spoke of the journey, the procession, the celebration, the food, the people. When he was done, I wanted to say, "But what do you think of the museum?" Fortunately, I stopped myself, realizing in the nick of time that he had told me. It's not about the museum, he'd said. It's about what happens there.

The National Museum of the American Indian is undeniably a beautiful place full of wonderful things. Its true value as a meeting point among cultures will be determined by what happens there.

Megan

Edwards

October 31, 2004