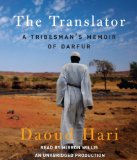

The Translator , by Daoud Hari (Read by Mirron Willis)

Millions of Americans learn about the genocide in Darfur from newspapers and network news shows and react with varying degrees of concern, but Dauod Hari's mesmerizing account of the atrocities occurring in his country is a surefire apathy buster. Born to Zaghawa parents in an isolated village in the Darfur region of Sudan, Dauod's pastoral existence is altered forever when his village is attacked by enemy helicopters and militia. A gifted linguist, the young boy offers to act as translator and guide for the assorted reporters, journalists and international aid personnel who eventually arrive. His assignments take him behind enemy lines, and he repeatedly escapes imprisonment and death. However, he eventually finds himself in a foreign jail, awaiting deportation and certain execution. A kindly jailer and a 100-pound note found in a secret pocket provide the means to get him back to his homeland, where his most dangerous adventures await.

The Translator is the very modest autobiography of a very courageous man who is trying to educate the world about the atrocities and suffering that continue to plague the people of Darfur. The displacement of hundreds of thousands of citizens, the starvation of entire villages, the murder of the men and the rape and murder of so many of the women and children are realities that Dauod and his countrymen have come to accept as routine. As horrific as these things are, though, he has not lost his sense of humor and his appreciation for the kindness of strangers. His account is very informative with his loving explanation of how the beasts of burden, donkeys and camels, fulfill their roles in desert survival. As he talks about his village and his relatives, he teaches the listener about the structure and values of Sudanese families and tribes. His observations about his foreign friends and employers are very insightful. He remarks, for example, that he'd rather guide journalists than NGO representatives because journalists are not so concerned with bureaucratic paperwork, and they always have plenty of alcohol.

In this age of global responsibility and global citizenship, Dauod Hari's observations help us learn how to understand each other. He rationalizes the torture he endured at the hands of sadistic Sudanese soldiers by pointing out that news coverage of torture in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib "gives crazy men permission to be crazy." Hari's comments about the nature of aid provide the kind of information that aid agencies can learn from. He remarks that the plastic and canvas shelters provided to the refugees, although well-intended, are unbearably hot.

Mirron Willis does Dauod Hari justice as his voice. His accented English is understandable, but the listener is required to stay engaged in the narration process in order to determine the intended meanings of some of the words. This is very effective, and makes The Translator an even more intensely personal account. Although Daoud Hari doesn't shrink from describing the horrors he and his countrymen have seen and endured, this is an uplifting and hopeful book and should be required reading for everyone, everywhere.

Ruth Mormon

10/24/06